Paired Rifles for Practice and Hunting

How to practice for your shoulder crusher without crushing your shoulder!

by J. A. Smith

How can our children learn to accurately shoot large caliber rifles? In the not too distant past, many of us had the luxury of putting hundreds, perhaps thousands, of rounds through one or more rifles in casual shooting during a typical year. Our experiences with this kind of shooting gave us an almost instinctive feel for where the sights should be centered and how far out we could reasonably expect to get a hit. Far fewer of today’s hunters have the money and access to undeveloped land needed for this practice. Indeed, most young folks in today’s world rarely get much time at the range, let alone a lot of informal shooting.

We’ll look at some ideas for an oblique approach to taming the recoil of your big game rifle by using a varmint caliber for much of your practice. This will help develop the fundamentals of posture, sight picture, trigger squeeze, etc. with less motivation to develop flinchitis from using your big gun for all of your practice. In brief, it is practicable to find factory loads where the trajectory of a small cartridge like the .223 Remington, .243 Winchester, and 6.5 Grendel matches the trajectory of a larger cartridge like the .325 Winchester Short Magnum, .338 Winchester Magnum, or .375 H&H Magnum to ranges beyond 500 yards. Reloading your own paired calibers gives much more flexibility in feasible choices. Also, by matching the scope, stock, action, etc., you can learn most of what you need to employ Kentucky Windage and Tennessee Elevation to accurately shoot the larger rifle to 200 -300 yards beyond the maximum point blank range.

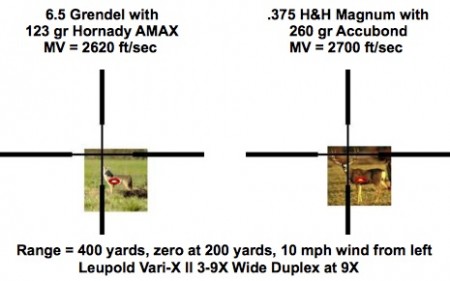

The sight picture for the 6.5 Grendel is the same as the 375 Magnum with the indicated loads. Deer and Coyote images courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service.

My father and uncle, and my grandfather were excellent shots. Their skills were developed through many years of casual plinking and real hunting. They each developed a philosophy about how to best stay at their peak as pressures of work and raising family took time away from shooting. “One rifle, one load” was the mantra my uncle Jerry often used when my dad and he debated about the best way to polish shooting skills for big game hunting. My father and I were on the side of using light loads in our deer rifles for practice and heavy loads for hunting.

My dad used a .375 H&H Magnum with hopes of an African safari one day and considered 300 yards a long shot. This meant that he did not need to use much holdover to hit the vital zone. He did, however, practice at shooting running game with lots of jackrabbit hunting with reduced loads.

My uncle, on the other hand, used a .264 Winchester Magnum on a sporterized Enfield action for his deer and elk hunting. He was able to harvest elk at ranges out to about 600 yards. The comparatively light recoil of the .264 allowed him the opportunity to use that 140 grain bullet for effectively all of his shooting without developing bad habits. His practice of taping ballistics charts to his stock way back in the late ’50s and early ’60s placed him among the first to routinely do this for sport shooting. As a result of his attention to detail and using a single load, he could really understand the performance of that load out to ranges beyond those which most of us could consider reasonable.

Fast forwarding from the debates between my father and uncle by close to fifty years, we see changes in ammunition and bullets that might allow a convergence of my dad’s and uncle’s philosophies. The emergence of high ballistic coefficient bullets in the .223, 6mm, 25, and the 6.5 calibers means that factory loads for many cartridges in these calibers are capable of matching the trajectories of large caliber rifles while keeping recoil energies below 10-12 ft-lb. The light recoil, quieter report, and reduced cost of these smaller cartridges allows us to shoot more often while using the same sight pictures we would for the larger cartridges.

There are multiple caliber combinations that can be shown to have effectively identical trajectories over the ranges of interest. For example, let’s look at one manufacturer’s catalog offerings. In this case the Hornady catalog shows several cartridge and bullet combinations that show very close to the same drop out to 500 yards.

| Cartridge | Bullet Weight, gr | Bullet Style | Muzzle Velocity (fps) | Approx Recoil Energy (ft/lb)† | Drop (in) at 500 yards* | Wind drift (in) at 500 yards** | |

| 0.223 | Rem | 75 | BTHP Match | 2790 | 4 | -49.3 | 25.3 |

| 0.308 | Win | 150 | SST | 2820 | 16 | -47.0 | 23.3 |

| 0.308 | Win | 165 | InterLock BTSP | 2700 | 17 | -50.8 | 22.7 |

| 30-06 | 165 | SST | 2800 | 19 | -46.2 | 21.5 | |

| 30-06 | 180 | SST | 2700 | 23 | -48.7 | 20.8 | |

| 0.375 | H&H | 270 | SP-RP*** | 2800 | 53 | -49.8 | 26.3 |

| †7.5 lb rifle, * 200 yard zero, sights 1.5” above bore line, **10 mph crosswind component | |||||||

| *** Superperformance load, Wind Drift per http://www.jbmballistics.com/ | |||||||

We can see from the table that both the wind drift and trajectory for each of these six loads are within five inches at 500 yards. This means that the .223 Remington with the standard velocity Hornady 75 gr BTHP has the potential of forming the basis for off season practice out to at least 500 yards for cartridges as powerful as the venerable .375 H&H Magnum! Further, the .223 Remington has less than one-tenth of the recoil energy as does that heavy .375 load.

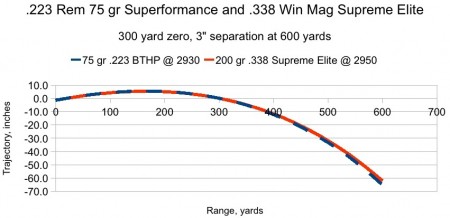

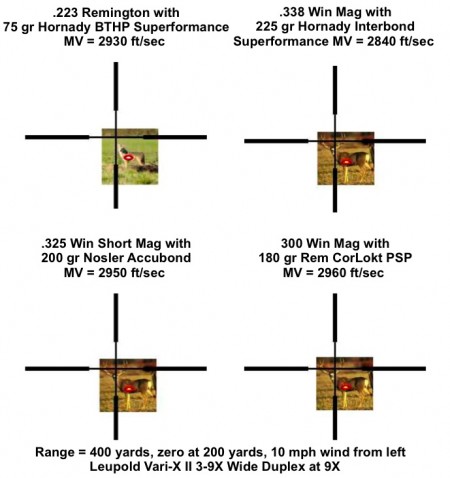

Alternatively, the 75 gr Hornady Superformance round in .223 Remington works for slightly flatter shooting variants in the .338 Winchester Magnum, the .325 Winchester Short Magnum, and the .300 Winchester Magnum cartridges.

Trajectories for widely varying calibers can closely match over ranges of interest. |

| Trajectory data calculated using Ammoguide Ballistics Calculator |

Matching trajectories from catalog information and calculated drift numbers by no means places us home free. The serious shooter needs to assure that each of his rifles are sighted in under the same conditions and to the same point of impact. The sight-in isn’t complete until the full battery is registered and sights adjusted to a common impact point at the longest range the shooter intends to hunt at. This last step may cause some divergence of an inch or two the 100 – 200 yard environment, but will assure that the trajectories are close enough at all ranges of interest.

The larger rifles are frequently used in dangerous game areas so the shooter becomes the one hunted often enough to be a consideration. This turnabout in roles evokes the well-founded admonition to practice with your rifle until you have an instinctive feel in shouldering, sighting and shooting a powerful rifle. How does this advice work with using as many as three different guns – one for practice, one for deer and elk, and the third for dangerous game territory?

We naturally want to mount optics that allow for quick, accurate shots in close. At the same time, we see that the cartridge is capable of some rather long shots. My Dad’s compromise was to use a simple 4X fixed power scope. This was the most popular scope during that period largely because it did balance ease of target acquisition with reasonably precise aiming for large game out to 300-400 yards. He also practiced on jackrabbits. Most of his rabbit shooting was in the stalking mode, which meant that he had plenty of opportunities to get the crosshairs into the right spot on fast moving animals from a few yards out to much longer distances. Naturally he got spectacular feed back when the .375 Magnum connected with a running jackrabbit!

Several large caliber rifles match trajectories with the 75gr .223 Rem Superformance load. Deer and Coyote images courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Following the Paired Rifle concept means that you want the same optic mounted on your light recoiling rifle and that the top-level handling characteristics like action, stock type, length of pull, rifle center of gravity, and sweet spot for eye relief are the same. My father’s experience with the fixed four-power scope suggests that a 3-9 power scope with a comfortable reticle will suffice provided that one practices enough at short ranges to become comfortable with getting the scope on target at the lowest setting. There will be time to reset the scope to the higher magnification for shots at ranges of greater than 75 or 100 yards. While the best answer to the basic rifle match is to custom build a set of two or three rifles that are the same except for the cartridge, this is likely also the most expensive option. Most of us won’t be able to spend the kind of money needed to exercise this one.

What compromises are available so that we can get the most with our limited budget? To get a better feeling for the compromises, let’s think through the sequence of loading, shouldering, and firing our heavy rifle. The single most important act is bringing the rifle to the shoulder and looking through the sight. We want that to be the same independent of the rifle. This means that the stock, length of pull, and eye-relief need to be the same. Still at the top level is the sight picture. We want it to be the same whether it is the heavy or the light rifle. Further, when stock type, length of pull, rifle center of gravity, and sweet spot for eye relief, and trigger are the same, you won’t know whether you are shouldering your light-recoiling rifle or your shoulder crusher until after the trigger squeeze.

A subtle, but significant, issue is the length of the action. There are stories of folks getting into trouble with bolt action rifles because they failed to run the bolt over its full length of travel. For example, you will do a lot of shooting with the .223 and develop muscle memory for how far the bolt turns and how far back you need to pull to eject the spent cartridge and load the new round. A short action optimized for the .223 has a much shorter stroke than the magnum-length action needed for the .375 Magnum. The length of required bolt stroke may be a factor in your choice of paired rifles and cartridges.

Now that we’ve touched on selecting paired rifle and cartridges, how do we make the best of the limited practice available in today’s world?

A) Use one of the reticles that have graduated tick marks corresponding to bullet drop at specified ranges. Especially useful are those that also have 10 mph wind bars corresponding with the drops. The next most convenient is likely a mil-dot reticle. Other reticles will work too, but may not be as easy to use because they don’t offer as many references or are overly complex for easy use. The choices are yours. The key is get one that you feel comfortable with for the kind of shooting you plan to do.

B) Use a laser rangefinder to help estimate Kentucky Windage and Tennessee Elevation. Yup, this might be seen as cheating by some, but most of us today don’t get the trigger time to do everything instinctively.

C) Use aids for visualizing sight pictures at a variety of ranges and wind conditions. Easy to reach resources include the companion COMPUTE SIGHT PICTURES and QUICKPIX on this website. A variety of reticles, magnification powers, and targets are there for you to see how the sight picture changes with range. QUICKPIX also lets you see how wind strength will affect your sight-picture.

D) Shoot whenever possible – preferably in the field and using typical hunting positions and ranges. Supplement the shooting with dry-fire practice, especially with the rifle with the longer bolt. Practice operating the action with the cheek welded to the stock. This will help keep the rifle on target and speed up any necessary follow-up shots. The whole point of this note is that you can get much of that needed experience using a rifle that has much less recoil, noise, and ammunition expense. Using that less powerful rifle for your long range shooting may give you a wider choice of places to shoot also.

E) Remember that shooting success is almost independent of bullet choice — bullet placement is all-important. Think about the care exercised by hunters using muzzle-loaders, single-shot rifles and bows in getting good shot placement. These folks have added incentive since a quick follow up shot is all but impossible when the target jumps and runs.

F) “Practice, practice, and more practice” is absolutely necessary. Work the rifle position and shooting holds at home with an unloaded rifle. Work at understanding the trajectory of your rifle both visually and by the numbers. Be attentive to the wind drift and visualize the Kentucky windage. Get out and varmint shoot with that lighter rifle during the off season. Remember that the most competitive shooters will put more rounds downrange in a single month than most of the rest of us will expend in a lifetime of shooting. All that practice makes them good shots. So get out there with your easy to shoot rifle and practice in a variety of hunting conditions, ranges, and so on. Complement the practice with the light kicker by getting in at least a few rounds with your heavy rifle so that you have the utmost confidence that it sends the bullet to the same place.

More examples of paired practice and hunting cartridges (Recoil energy with 7.5 lb rifle):

Practice: .223 Remington (300 yard zero)

| Cartridge | Brand | Bullet | Muzzle Velocity, ft/sec | Approx Recoil Energy (ft/lb) | 500 yd drop (in) | 500 yd drift (in) |

| 223 Remington | Federal | 77 gr MatchKing | 2750 | 4 | -38.8 | 28.8 |

| 375 H&H Mag | Hornady Super | 270 gr SP RP | 2800 | 53 | -36.1 | 26.3 |

Practice: 6.5 Grendel (300 yard zero)

| Cartridge | Brand | Bullet | Muzzle Velocity, ft/sec | Approx Recoil Energy (ft/lb) | 500 yd drop (in) | 500 yd drift (in) |

| 6.5 Grendel | Hornady | 123 gr AMAX | 2620 | 8 | -36.4 | 20.4 |

| 0.338 Win Mag | Federal | 250 gr Partition | 2660 | 40 | -36.4 | 21.8 |

| 375 H&H Mag | Federal | 260 gr Accubond | 2700 | 45 | -35.0 | 21.2 |

Practice: .233 Remington, 6 mm BR or .243 Winchester (300 yard zero)

| Cartridge | Brand | Bullet | Muzzle Velocity, ft/sec | Approx. Recoil Energy (ft/lb) | 500 yd drop (in) | 500 yd drift (in) |

| 223 Rem | Hornady | 75 gr BTHP Superformance | 2920 | 5 | -31.4 | 23.2 |

| 6mm BR Norma | Lapua | 90 gr Scenar HPBT | 2950 | 7 | -30.0 | 20.8 |

| 243 Winchester | Federal | 95 gr Ballistic Tip | 3030 | 9 | -28.9 | 21.2 |

| 300 Win Mag | Remington | 180 gr Core-Lokt PSP | 2960 | 30 | -29.5 | 20.3 |

| 300 Win Mag | Federal | 180 gr Partition | 2960 | 30 | -28.4 | 18.5 |

| 300 Win Mag | Hornady | 180 gr Interlock SP | 2960 | 30 | -29.9 | 21.1 |

| 300 Win Mag | Winchester | 180 gr PowerPoint | 2950 | 28 | -29.5 | 20.3 |

| 300 Win Mag | Remington | 180 gr Ultrabonded | 2960 | 30 | -30.8 | 22.5 |

| 325 WSM | Double Tap | 200 gr Barnes TSX | 2970 | 34 | -29.9 | 21.2 |

| 325 WSM | Double Tap | 180 gr Barnes TSX | 3095 | 31 | -28.7 | 22.6 |

| 325 WSM | Winchester | 180 gr Ballistic Silver Tip | 3060 | 30 | -27.4 | 19.3 |

| 338 Win Mag | Hornady | 185 gr GMX | 3080 | 34 | -27.5 | 20.2 |

| 338 Win Mag | Winchester | 200 gr E-Tip | 2950 | 35 | -30.2 | 21.2 |

| 338 Win Mag | Barnes | 225 gr TTSX | 2800 | 38 | -31.1 | 18.2 |

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Steve Hunter, an accomplished competitive shooter and hunter, including the odd African experiences, for his constructive criticism and to Terry Overly of pioneeroutfitters.com, an experienced guide and outfitter for his insight into large game hunting and how most guided hunters function.

About the Author: Mr. Smith is an avid shooter and reloader who has competed in the NRA 2700 matches (.22, .38, & .45 bullseye shooting) as well as international style air pistol. He is a Vietnam Veteran and an NRA Life Member and has helped instruct rifle and shotgun for the Boy Scouts of America shooting sports. He recently retired from the University of California after more than thirty years dedicated to research and development of a wide variety of weapons.

###

All rights to this material remain with the author until publication.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.