Most of us reloaders stay well within the boundaries defined by commercial load data. This is an important safety practice and costs very little in terms of real performance in the field. Test this by using your favorite ballistics calculator to estimate the drop for the starting load (typically 5-10% below max) and the maximum load at 300 yards. Then compare that to the holdover, if any, you might need to get the bullet inside the canonical 10” vital zone. The bottom line is that even though the starting load drops a bit more, it won’t normally make a big difference in your sight picture at customary hunting ranges. Similarly, the bullet’s lethality is very close to the same at both the starting and the maximum loads.

This very safe practice gets stressed, however, when a new powder or bullet appears on the market. Unless you happen to shoot one of the popular calibers the powder and bullet companies target their powder for, you will wait a long time before you can get commercially vetted load data. Similarly, long-range target shooters frequently press the maximum load ceiling to get the slight added performance edge that can make the difference between winning or losing a contest. How do you work up safe loads when you happen to be in one or both of these groups?

An Easy Test

A lot of folks use the classic primer inspection, loose primer, smearing of case head into bolt face, and so on to get a feel when their lots are a tad on the hot side. Even though some controversy exists regarding reliability, the general assumption is that these signs start to become evident when pressures exceed something like 55,000 psi and become clearly obvious at above 63,000 psi. The reader must interpret for himself what is meant by “evident” and “clearly obvious” since a fair amount of judgement is needed to make use of these techniques.

Perhaps the most accurate pressure sensing systems available to the handloader are strain gauge – based systems like the Pressure Trace System by Recreational Software, Inc. These systems unfortunately cost as much as many of the rifles we use. The significant cost combined with the challenges of using the systems correctly place them more or less out of reach of the average handloader.

Measure the diameter at the web

Case head expansion uses less sophisticated equipment and is a tool one can add to the set of things to check when trying to infer pressure levels. In brief, one measures the change in diameter of the case at the head – between the extraction groove and the main cavity of the case. Interestingly, we are doing a measurement that is analgous to, but not the same as, the the change in length of crush cylinders classically used by industry.

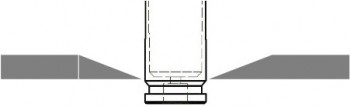

The anvils of standard micrometers tend to be large enough that one tends to get the pressure ring rather than the base diameter measurement. As the illustration above suggests, a blade micrometer is the best tool for this measurement but they tend to cost nearly as much as the strain gauge pressure trace system. This leaves standard calipers as the remaining measurement tools – and these have blades!

The micrometer anvil is too large to measure the case head diameter. It bridges either to the rim or the pressure ring

Calipers, of course are accurate to the nearest mil (0.001 inch) meaning that we will need to see more than one-half mil expansion to detect any increase in diameter.

Here’s what we do:

- Measure and record the diameter of several factory loads or trusted handloads with headstamp always in the same position.

- Take the average of these measurements.

- Shoot these cartridges recording all relevant information as usual

- Measure the new case head diameters using the same technique as above.

- Take the average.

- Subtract the average unfired diameter from the average diameter of the now once-fired cases.

This average change in diameter gives a baseline for your brass and your rifle.

The next step also needs to be done with unfired brass and must be the same brand of brass that you used to establish the baseline. Do the same before and after measurements for the loads you develop while keeping the brass sorted by charge weight, bullet, etc. The change in diameter should be the same as or less than your baseline. If larger, then you should strongly consider reducing your load.

I developed an example baseline using nine Remington .243 Winchester 100 grain factory Core-Lokt® rounds. The average case head expansion measured with the dial caliper was 0.002 inches. We compare this with the expansions calculated by VarmintAl (image in the last section of this note.) and find that this factory load has an expansion very close to his calculation for the SAAMI maximum pressure for the .243 Winchester.

While it appears that this brass was a little softer than the material VarmintAl modeled, we would have been astounded if there had been a closer correlation. Factory loads are generally set to run slightly below the SAAMI pressure and VarmintAl modeled generic cartridge brass. Each manufacturer uses a unique processing schedule and gets brass stock from different sources. The strengths are different for each brand and even for each lot. This is why one needs to baseline using the same brand, preferably the same batch, of unfired brass for baseline and load work up when using this method.

The method may not work for you, but the same can be said of reading primers and brass smears. Try it and see if it works! If it does, then you can add it to the other techniques you use to tell if the loads are getting close to doing bad things to your rifle.

The remaining notes in this sections expand the discussion of pressure sensing in rifles, adds a more detailed process to use when one does a ladder or Optimal Charge Weight test, and concludes with a discussion of why the case head expansion technique can work. The detail adds up but the principles are the same as we have already discussed.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.